Warning: I am not a musicologist. I am just interested in music. Do not quote me or act based on the information available on this page. You can collect and collate information in the same way as I have. These are from public sources such as sarangi.info, itcsra.org, musicindiaonline.com and others. This is only an indicative article and I do not claim its correctness or its completeness. I don't want credit for anything. Thank you.

TODI

Soul Food for Ascetics

The Raagas of the Todi Thaat (Root) are regarded with much apprehension. Extremely hard to handle by most musicians, especially instrumentalists, it is also not the easiest to fully unravel by the listener. One practical reason is, of course, that the Raagas that owe their existence to this Thaat are all executed in the morning when most concerts are not scheduled anyway. Thus the rarity.

As a result, names like Khamaj, Bageshree and Bihag etc. are far more familiar as they appear in the evening/night when people are possibly more disposed to relax and listen.

Highly cerebral and intellectual Raagas like Todi do deserve much more than a cursory glance. Two quick appetisers - here and here.

Todi is highly reflective and meditative. We visulize a merging with a greater consciousness, an endless time, fleeting and evanescent life-blips. I am aware of one musician who was sucked in so badly by this Raaga that he possibly went mad. The shades and depths of this Raaga are not for the timid.

They emphasize, in my mind, a stern and uncompromising internal focus on something elusive but clearly present. In short, the soul.

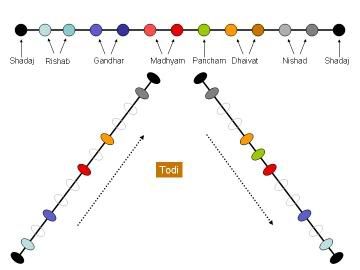

The Todi for Hindustani Classical corresponds to Hanuma Todi of the Carnatic school, whose Todi is different. I digress.

This figure explains the strange undulations of Todi in the ascent and descent. The symmetry is broken by the unexpected and delicately introduced Pancham. An analogy might be the Teevra Madhyam of Yaman which is conspicuous by its sparing use. The determined non-usage of Pancham results in Gujari Todi, which also has a different lilt. But it is not as easy as that. If it were, the mere removal or addition of notes ought to result in millions of new Raagas. This is not true; some combinations are indeed considered 'unmusical'. The manner of exposition is also important. A fast Bilaskhani Todi will sound jarring without a proper buildup or a slow Brindavani Sarang is meaningless. Or a Nand without adequate interspersing of silence violates its essence, though it may sound okay.

Another simply classic example: the Sarangi of Munir Khan.

Here you have Faiyaz Khan singing Todi.

A much longer version by Parveen Sultana is available here. If you listen carefully, you will find a few errors, which merely shows how difficult this Raaga is, and not necessarily the caliber of the artiste. These things happen.

Bilaskhani Todi is a misnomer, though understandably so. It technically belongs to the Bhairavi Thaat. It's pathos must be remarked upon. The story is that as Bilaskhan, the son of Tansen, created this Raaga at the funeral of his father. You are unlikely to find a more brilliant example than that of the late Pandit Nikhil Bannerjee's Raga Records production example (no audio here, sorry).

Here is a beautiful example, otherwise, by his student Kushal Das.

What marks the special searing pathos of Bilaskhani Todi? First is the missing Madhyam on the ascendent, and the pair of Gandhar and Pancham. Further, while ascendng, if Madhyam is touched, a descent is forced. And then the quadra-set of Dhaivat, Nishad, Nishad and Madhyam. Odd? Hmmmm... that is the soul-disturbing pain of Bilaskhani Todi, an extremely moving

Raaga. Here is Amir Khan.

From an unknown manuscript, unlikely to ever see the light of day, Bilaskhani Todi speaks as the flames in a pyre:

As we lick this pyre singing Komal Rishabh, we wonder at our task. As we creep over his body, we peep at his face and reach for the Pancham in exclamation, astonished at his nobility. Yes, he knew us, your Father, and now we know him.

Komal Rishab Asavari Todi. The challenging Raag derives its name from the use of Komal Rishab rather than the Shuddha Rishab of Asavari. Asavari is another Thaath from which Raags like Jaunpuri, Darbari and Adana emerge. You'll like this.

Some argue forcefully that it belongs to the Bhairavi Thaat. These little differences make for enjoyable analysis.

Bhupal Todi is merely Todi with the film of Bhupali overlaid. Specifically, the removal of Madhyam and Nishad. Thats the mathematics, but, as explained previously, that doesn't suffice.

Here are two more important variants.

Bahaduri Todi Mallikarjun Mansur uses both Rishabs with gravity and care. You will also find both Madhyams, the lower an accent from Bilaskhani Todi. Not for the faint hearted.

And Gujari Todi

Here you have a lovely piece in Todi by Abdul Latif Khan. Worth many listens.

Asa Todi, or just Asa, is a rarity mostly found in Sikh Shabads. I found a nice one by Bhimsen Joshi. It is a blend of Asavari and Todi.

Two relatively popular Raagas that derive fom Todi are Madhuvanti and Multani. Multani is restless, while Madhuvanti is sweet. Multani shares the notes of the base Todi, while Madhuvanti deviates in the use of Rishab. One may argue it does not belong to the Todi Thaat

Here is a Sarangi piece by Nathu Khan in Multani

And here is Inayat Shah on the Dilruba playing Madhuvanti

We end with this Todi and here are Ustad Bismillah Khan and the late Pandit V G Jog (who explained Todi to me and a young Dutch violinist so many years ago in a small room in Kolkata, which we then played together somewhere and made a mess of.)

Enrich your lives and those of the next generation now! Listen to Indian classical music!

Cordially and Goodbye.

VM

6 comments:

Nice blog. Keep writing (re: Hindustani classical).

One question that confuses me: Why do you mention Bilaskhani Todi and Brindavani Sarang in the same sentence ? Are they related ?

The reason I ask is because this other performance by Amjad Ali Khan consists of an alap (& jor) in Bilaskhani Todi, followed by a gat in Brindavani Sarang. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B00000FXZO/sr=8-5/qid=1145022640/ref=sr_1_5/102-2663039-2799325?%5Fencoding=UTF8

Thanks for your insight.

Dear Mr. Sheth

They are not related.

Concidentally, Amjad Ali Khan plays both precisely to highlight the point I was making.

BT must be played slowly - he does. Brindavani Sarang must be played at a quick tempo - he does.

I suspect he wanted contrasts and this pair was a good choice

Regards

Vasudev

interesting stuff. can u throw any light on the similarities between maduvanti and dharmavati?

Just some comments:

TODi of hindustAni idiom corresponds to ShubhapantUvarALi (or ShivapantUvarALi) of the karNAtik idiom. Not HanumatODi, as is mentioned in the article. karNATik HanumatODi (or janatODi or simply, tODi) uses notes from the bhairavi thAt. It is a sampUrNa-sampUrNa rAga of the bhairavi thAT.

Also madhuvanti and dharmavati are close. Madhuvanti is auDava-sampUrNa rAga (with rSabha and dhaivata varjita in the ArOhaNa) whereas dharmavati is sampUrNa-sampUrNa rAga.

Have you heard of the site where you can download free music? Check it out at avaleigh.co.uk

Just a note:

Bilaskhani Todi is NOT AT ALL a part of the Bhairavi thaat. It has the same notes, yes, but any structural similarity to Bhairavi ruins Bilaskhani Todi, the most important characteristic of which is the interaction between the g and r swaras.

Post a Comment